Remembering Lee Alexander McQueen: A Decade Later

Source: WMagazine

When Lee Alexander McQueen, CBE took his own life on Feb. 11, 2010, the fashion world was in complete shock. 2020 marks the 10th anniversary of McQueen’s death, and yet his clothes are more relevant now than ever before. The work that McQueen created for his eponymous label is unique in many ways: his clothes exemplified and personified his life story with his unique take on beauty and fascinatingly frightening collections. Not only was his work deeply profound, but it also brought out a range of emotions few other designers could ever hope to replicate. The cult-following of his 18-year career rivals no other.

The British designer got his start in the fashion industry in an unorthodox way—he had no formal background in designing clothes. However, the talent he possessed was unlike any had ever seen. After dropping out of school and working various stints at London tailor shops Anderson and Shephard and Gieves and Hawkes, he moved on to working with costume designers Angels and Bermans. A close friend of McQueen claimed in the 2018 documentary “McQueen” that his tailor work granted the designer the ability to never measure his models; he could just tell measurements by studying a person’s body. After attempting to get a job at London’s prestigious Central Saint Martins fashion university, they instead suggested he enroll as a student. In 1992, McQueen received an M.A. in Fashion Design.

Source: Dazed

McQueen’s enrollment at Central Saint Martins gave way for his graduate collection to be shown at British Fashion Week. The collection titled “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims” referenced Rippers’ 1888 Whitechapel victims. McQueen was greatly influenced and fascinated by the dark romanticism of the 19th century throughout his career. According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute curator Andrew Bolton, one of McQueen’s relatives owned an inn that housed a victim of Jack the Ripper. McQueen’s inspiration for his hair sewn into the clothing came from Victorian prostitutes selling locks of their hair for people to give to their lovers. Sitting on the floor of the catwalk was eccentric journalist and stylist, Isabella Blow, who immediately bought the entire collection off McQueen; Blow became a lifelong friend and advocate for McQueen’s work.

Source: Vanity Fair

Lee Alexander McQueen (left) and Isabella Blow (right); Photographed by David LaChapelle in 1996

As McQueen’s status elevated, he continued to push the boundaries of merging fashion and art. McQueen’s work took the approach of performance art—the clothes were not meant to be replicated nor were they meant to be sold for wearing. McQueen said, “I think there is beauty in everything. What ‘normal’ people would perceive as ugly, I can usually see something of beauty in it”. McQueen often said that he wanted his runway shows to gain as much attention as possible, whether the press gave him good or bad reactions mattered little to him. His larger than life personality similarly fit alongside the shock of the clothes he created. It earned McQueen a reputation for being unpredictable.

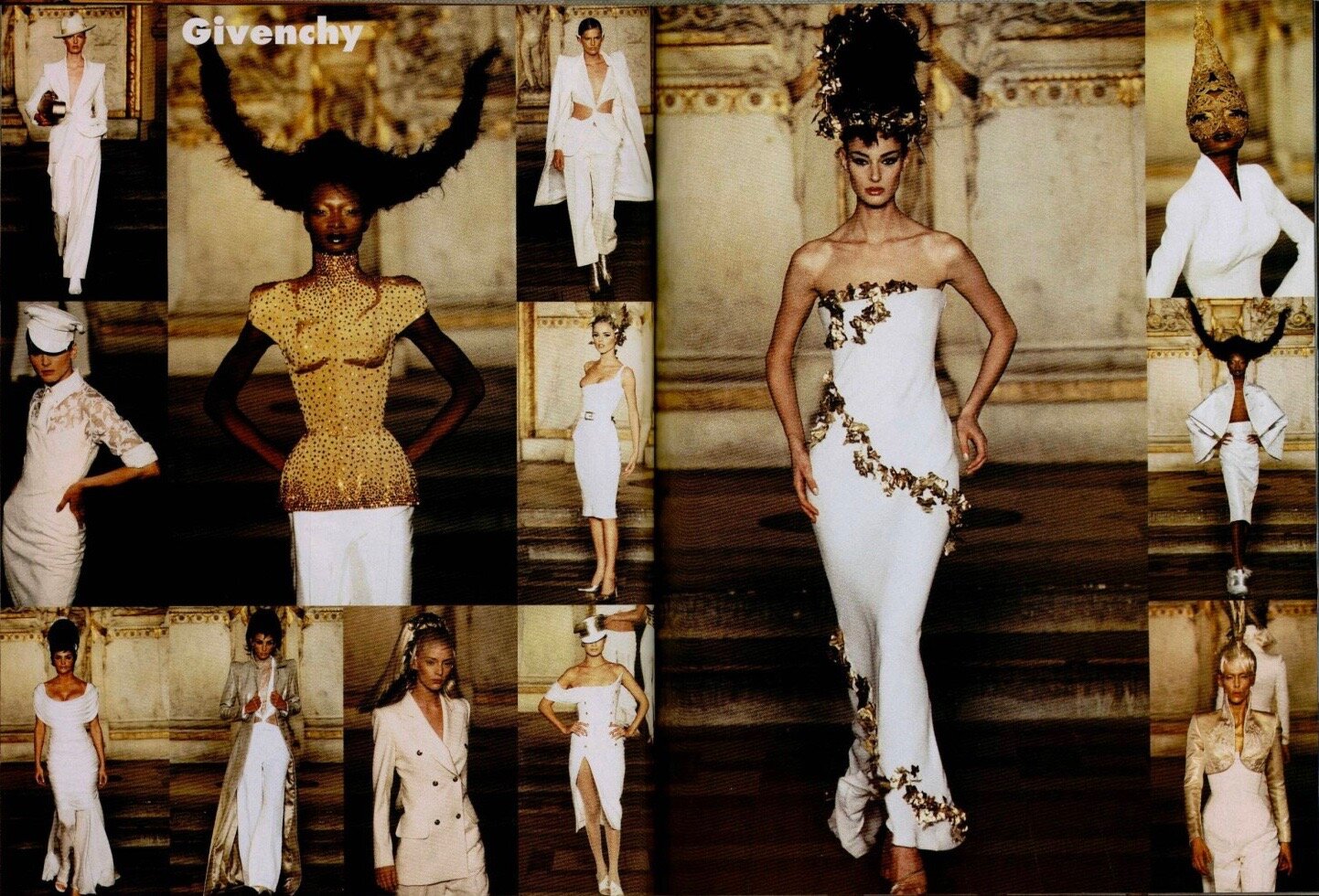

After only four years on the circuit, McQueen was appointed creative director of Givenchy in 1996, succeeding John Galliano who moved to Dior. The house of Givenchy and McQueen had a tumultuous relationship. McQueen defied expectations and brought his dark romanticism, opulence, and over the top nature to Givenchy. Earning the ire of the French press, they nicknamed him “l’enfant terrible” and “the hooligan of English fashion.” His first Givenchy collection, “Search for the Golden Fleece,” came about in McQueen’s mind after attributing the Givenchy logo with classical Grecian style. The entire collection was done in gold and white and included body corsets, humongous hair in the shape of horns, and immaculate tailoring. It certainly was not clothing to be worn by starlet Audrey Hepburn that the Maison was known for, but it was indeed radical and beautiful.

Source: Pattern Vault

Givenchy Spring/Summer 1997

“I think there is beauty in everything. What ‘normal’ people would perceive as ugly, I can usually see something of beauty in it”

Many times, McQueen’s nontraditional approach was portrayed as being controversial in the themes of his collections. His 1993 A/W collection “The Taxi Driver” introduced his famous “bumster” trousers that showed the top of the butt; however, that wasn’t the primary intention. McQueen said, “That part of the body—not so much the buttocks, but the bottom of the spine—that’s the most erotic part of anyone’s body, man or woman”.

1995 A/W saw “The Highland Rape,” which at the time was widely criticized as being misogynistic. The runway featured women staggering helplessly on the runway in tattered clothes and several looks showcasing women’s breasts exposed; many people walked out of the show. However, the conception of the show was more of a personal nod to McQueen’s Scottish heritage; it was a social commentary on the pillaging of the Scottish by the English. It also was a confessional of his own experience with abuse; McQueen and his sister were both abused by her husband. McQueen said, “I design clothes because I don't want women to look all innocent and naive. I want women to look stronger. I don't like women to be taken advantage of. I don't like men whistling at women in the street. I think they deserve more respect. I like men to keep their distance from women, I like men to be stunned by an entrance. ... I want people to be afraid of the women I dress.”

Source: Thread Magazine

One of the most talked about shows to this day is McQueen’s 13th collection. Ahead of its time, his 1999 S/S collection titled “No.13” focused on the convergence of technology with humankind. The show ended with Shalom Harlow emerging on a spinning wooden platform in a white strapless tulle dress. She danced and moved along with the robots in time with the music. Then the robots, two industrial sprayers made by Fiat, sprayed the dress and Harlow with black and yellow paint. McQueen, known for being a champion of diverse beauty, also had Paralympic amputee Aimee Mullins walk in the show on wooden legs McQueen had specifically carved for her.

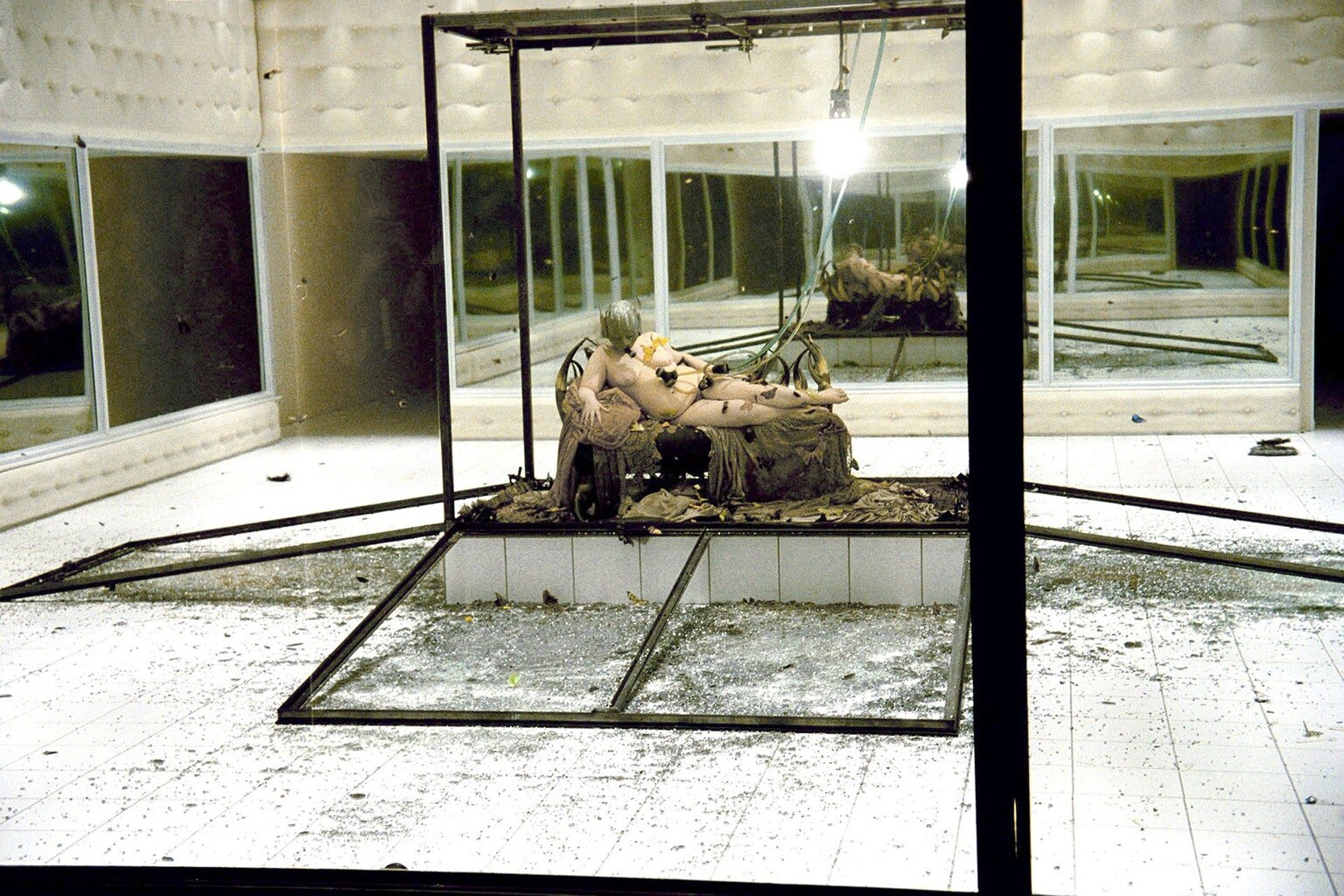

Other fantastical collection concepts include 1998 A/W’s “Joan” ending with a model circled in a ring of fire; 2001 S/S’s “Voss” ended with a glass box that shattered and opened to a naked figure of writer Michelle Olley covered in moths in the recreation of Joel Witkin’s 1983 “Sanitarium”; and 2006 A/W’s “Widows of Culloden” featured a life-size hologram of Kate Moss in yards of fabric.

Source: Vogue

“I design clothes because I don’t want women to look all innocent and naive. I want women to look stronger. I don’t like women to be taken advantage of. ... I want people to be afraid of the women I dress.”

McQueen’s brilliance certainly made people take notice. The designer’s creativity and ingenuity can be likened to surrealist designer Elsa Schiaparelli, who similarly pushed the boundaries of what constitutes as fashion. He was one of the youngest designers to achieve British Designer of the Year, which he won four times between 1996 and 2003. In 2003, McQueen was honored with a CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) and named International Designer of the Year by the CFDA.

The year following his suicide, The Met Museum held its annual Met Gala which highlighted McQueen’s genius. Titling it “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty,” the exhibition was extremely popular and resulted in record attendance for the museum. It was so successful that the exhibition made its way to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2015 where it received similar recognition and shattered attendance records.

From humble beginnings to stardom in his early 20s, the world has watched with curiosity from the start of McQueen's career. McQueen’s vision from the late ‘90s to the early 2000s is incomparable to many designers and creative directors working today. While it has been a decade since McQueen’s passing, his life’s work and ingenuity will continue to inspire fashion for generations to come. McQueen once said, “Give me time and I'll give you a revolution.” A revolution he certainly gave us.

Source: Kim Jones Instagram