Communing with Clouds

*Article from Lexington Line’s Autumn/Winter 2021 Issue, pages 20-22

Check out the full issue here.

It’s 1997, and an 11-year-old boy steps on stage for the first time. He’s at The Quarterdeck restaurant in his hometown of Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, and his father, a locally known drummer, sits behind him in anticipation. The boy steps to the mic, stares into the crowd, lifts up his harmonica, and plays the first note of “Sweet Home Alabama.”

Cut to 2020. Trevor Hall, now with nine studio albums and 20 years of touring under his belt, kisses his wife and newborn son seconds before greeting a sold-out crowd at Red Rocks Amphitheatre.

But in those 23 years, Trevor Hall became more than a great artist. For me, he became the older brother I never knew I needed. As his sister-in-law, I witnessed many changes in his life and accumulated many memories of my own, so I felt compelled to hear the other parts of his life story.

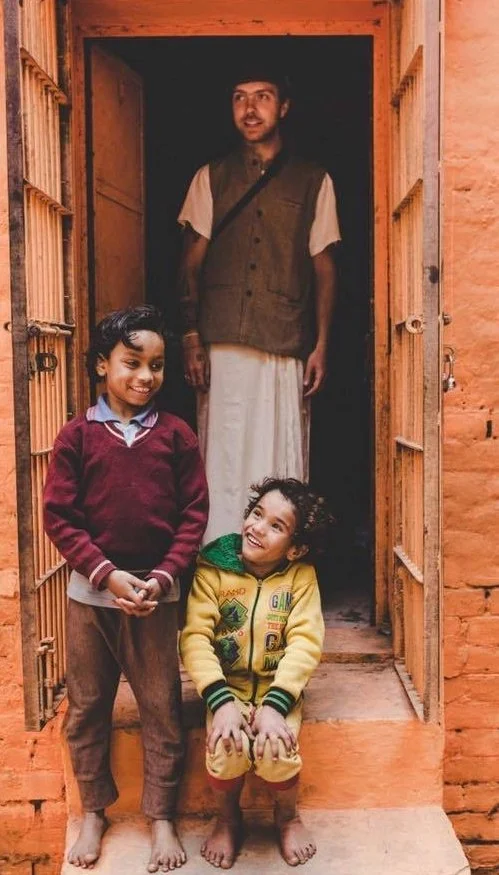

Trevor at his ashram in India

As a teenager attending Idyllwild Arts Academy, a boarding school in Idyllwild, California, Trevor became obsessed with art and music. He majored in classical guitar and began writing songs. He was also inspired by a friend’s picture of the Hindu saint Neem Karoli Baba and became heavily influenced by Hinduism.

In his senior year, he was briefly signed to Geffen Records, and after graduating, he began a relentless touring schedule that would persist for years. He released several albums, and his song “Other Ways” was included on the soundtrack for Shrek the Third. He eventually moved to a Hindu temple in Southern California and lived there for roughly a decade. As both a well-established musician and devoted acolyte in an ashram, Trevor would proceed to live a double life for most of his career.

“One moment I was traveling everywhere: music, late nights, bars, living this vagabond lifestyle,” he remembers. “Then I had to switch to a completely devotional life.”

Seamlessly switching between singing bhajans (Hindu devotional songs) to singing his own hits was a little complicated.

“Those transitions were very tough for me. Once I settled into being on the road or in the ashram, I was fine, but those transitional periods spurred so many questions of ‘Who am I?’ or ‘Am I this or am I that?’” Trevor says.

Things settled down eventually. I vividly remember Trevor when he woke up on his thirtieth birthday, ran down the stairs, and exclaimed how happy he was to be out of his twenties. For Trevor, his thirties symbolized permission to relax into his life.

“When you’re growing up, you’re so intense about everything; I still have that intensity, but to a much lesser degree,” he says. “When I hit 30, and as I’ve grown more into my thirties, there’s been a ridding of what’s not important. Things got a little simpler in my focus, my direction, and I think it was the letting go of that unhealthy intensity of my twenties.”

He ultimately left the ashram but acknowledges how the years he spent there greatly influenced the person he is today.

“When I left the ashram, suddenly I had to create that devotional energy for myself. It’s almost like I was a baby bird being set up to fly for the first time—I needed to learn how to fly on my own,” Trevor explains. “During my formative years, I was so affected by my external environment. Now I feel as though my spirituality is inside of me, so I can relax. I’m not so concerned with what’s going on around me anymore, which I think gives me a sense of freedom as an artist.”

Aside from his commercial music, Trevor has released a myriad of devotional songs throughout his career. At first, his change in environment made it harder for Trevor to find inspiration for devotional music, but now, he feels that moving out of the ashram only deepened his devotion.

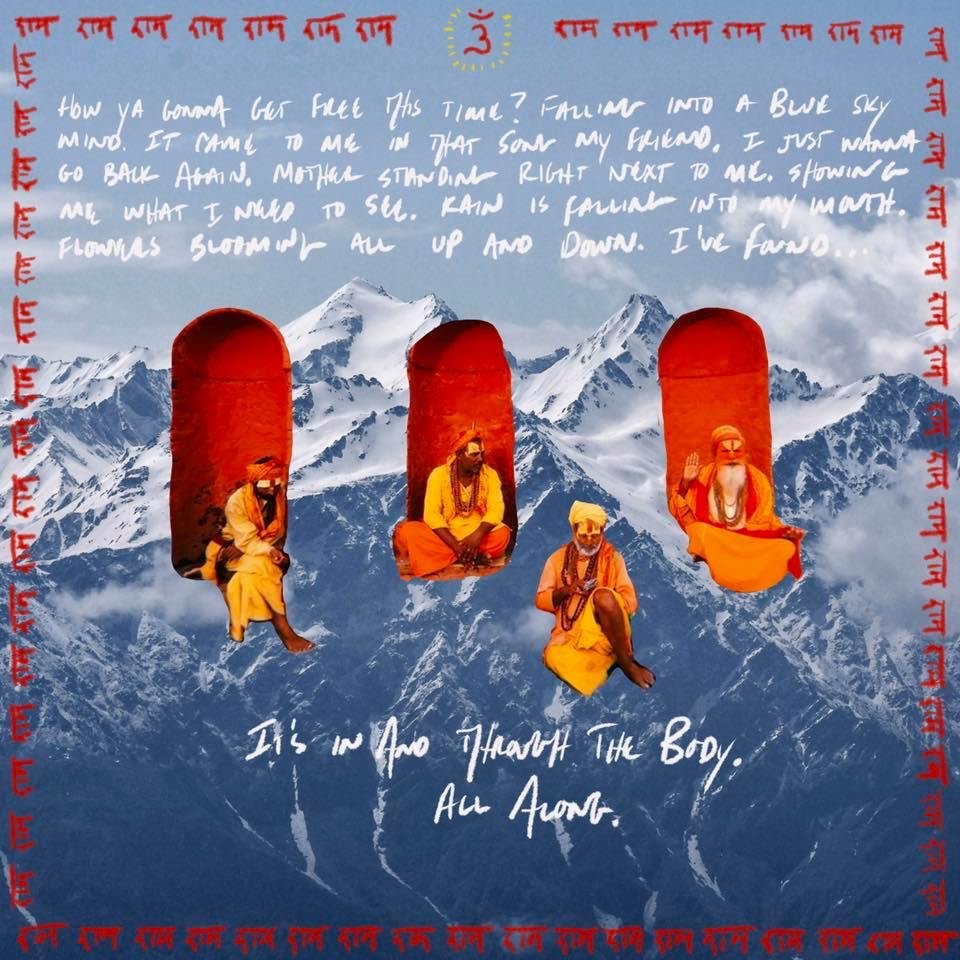

Art by Trevor Hall

Trevor’s latest album, In and Through the Body, is influenced by his spirituality. He uses poetic imagery to reflect his ideas about consciousness. On many songs, you can find vivid imagery of clouds forming and disappearing, which connects to a common theme in Hindu spirituality.

“Our consciousness is compared to the sky,” he says. “[People] may identify with a sunny sky or a dark sky, but as a whole, these clouds moving through the sky are essentially the thoughts and emotions that control our minds and mental state.” To this day, he is still learning how to be less affected by the clouds of emotion that move through his consciousness—how to witness them, honor them, and watch cycles change in your own mind.

“Great storm clouds holding rain/It's part of nature to hold a bit of pain,” he sings in “Great Storm Clouds.” “All in all, that rain falls/and then we watch a new thing grow.”

For Trevor, clouds in the sky remind him to contextualize his negative thoughts—to honor them as they pass. “It’s seeing the fullness of all our different emotions and states but seeing it from a space of neutrality.”

Apart from being a creative milestone for Trevor, In and Through the Body was also a significant career achievement. Back when Trevor and I lived under the same roof several years ago, I remember waking up every morning to Trevor playing Bon Iver’s record, 22, A Million, every day. So, when Brad Cook, the producer of 22, A Million, asked to produce Trevor’s next album, he hopped on a plane to Raleigh almost immediately.

Trevor and Brad Cook (middle) after completing In and Through the Body. Photo by Trevor Hall.

“It was definitely a huge step for me personally and creatively. I have doubts just like everybody else, but it’s all just my ego. The ego can be really puffed up or the worst negative self-talk, but both are harmful,” Trevor says. “There was an acknowledgment of maturity that came with this step in my career.”

Brad brought in his brother, the folk artist Phil Cook, to contribute musically, and the brothers teamed up to help Trevor make In and Through the Body into a modern masterpiece.

Trevor has made good on his opportunities over the years and developed tremendous insight in the process. He loves touring and still finds himself dividing his time between being on and off the road, which is always a little stressful.

“Coming off tour is hard. When you’re touring, it’s very clear what your purpose is: you get up, travel to a city, play a show, and repeat,” he says. “Even when you’re tired, at least you have a solid purpose when you’re on the road. Then, when you come home, that’s what we call ‘post-tour depression’—it's quiet, and suddenly there’s nobody around. It makes you almost doubt your purpose.”

But stress and hard work are part of the deal for any serious artist.

“No matter who you are, what kind of artist you are, what kind of art you engage in, you’re going to face so much pressure [...] and that can really distract you,” he says. “The craft itself is the ultimate teacher. The craft is the question and the answer, it’s all in one, one in all. You are going to get distracted, you are going to get pulled away, but you can always find your craft again.”

Trevor in the studio with his son / Photo by Trevor Hall

He missed touring during the quarantine, but used the time constructively—he bought a house, got a dog, released an album that sat comfortably on Billboard’s Top 20 Folk/Americana Albums chart, and most importantly, welcomed his first child into the world.

“Everybody tells you how much having a child changes your life, but it’s one thing to hear about it and then a whole different thing to experience it,” Trevor says. “I’m just grateful for the time and energy I was able to give into—literally—nesting and making a good space for our son to come into.”

In a world of social media and social disconnect, it’s easier than ever to lose yourself, Trevor attests. Young people are under more pressure than somebody like Trevor, he says, because he didn’t have to grow up in the social media era.

“Sure, it may be easier to get your art out there, but you’re also up against a lot.”

As an artist, it is more important than ever to remain authentic. The best advice Trevor can give artists looking to start their creative careers in the twenty-first century?

“Protect your energy. Protect your craft. Trust it and let it guide you, wherever it takes you.”