The Ever-Changing World of Graffiti

Graffiti is art that refuses to be ignored. It requires unique and tedious techniques; it utilizes an unconventional medium of spray paint, and it’s mainly created on canvases that everybody can see. Graffiti is widely accepted now and seen heavily in New York City, so much so that people want to take pictures in front of it and hire artists to create a graffiti mural for their spaces. With that said, it has been shunned and looked down upon in the past. It would be painted over or washed off subway cars, and people would get arrested for defamation of property. So, the burning question is: how did we go from arresting to hiring and compensating people for the same artwork?

Graffiti initially started with just a few words sprayed on the walls outside inside subway stations. Taki 183, a bored teenage artist from Washington Heights from the late 1960s, is the one who started tagging as if it was his career. The now ever so popular tag consisted of the combination of “Taki,” the nickname of his Greek name, Demetrius, and “183,” his street number. From lampposts to fire hydrants, the “graffiti forefather” was painting everything in his sight. He quickly fell in love with the rush of tagging and enjoyed seeing his name everywhere. Slowly but surely, more and more tags began to be seen around the city, and it was no longer just Taki 183 .

ZEPHYR, a well-known graffiti artist from the ‘70s to ‘90s who worked with artists like Futura 2000 and Jean-Michel Basquiat, can also relate with Taki 183’s obsession. “Even after all these decades I still love to paint ZEPHYR pieces. It’s like being in the zone: very peaceful, focused and having fun.” ZEPHYR states.

Then, from 1968 to 1972, graffiti quickly began to change. Artists began experimenting with new fonts, like bubble letters and script. New objects and shapes were added to tags like eyeballs, people, flowers, and more. Artists wanted to stylize their defiance and to communicate their messages in a more powerful way. Simple tags were turning into true masterpieces, and soon were seen anywhere and everywhere. People would see pieces on the side of subway cars, on the walls of buildings, in tunnels–anywhere you can think of. This is how artists grew their reputation, as well as how everybody interacted with one another.

“We had black books that we passed around with each other. We would do our own work in them, we pass it to others, and then sometimes we do their name for them in our style. It’s like we gifted each other letters we can use as inspiration in our next piece,” says Lady Pink, an artist who grew up in Queens, NY. Lady Pink has been creating art ever since the age of 5: painting tiny mushrooms and fairies. “My friend SEEN just came into school and said: ‘Here. This is your name now.’ And I was like, okay,” she laughs, “and that’s how I got the name Lady Pink.”

Even though fellow New Yorkers didn’t mind the graffiti takeover, it was something that was brought to the attention of the mayors of New York City in the 1960s to late 1980s: Mayor John Lindsay, and Mayor Ed Koch. They, as well as their colleagues, made sure to crack down on graffiti around the city, as it was seen as a contributor to the “urban problem.” Throughout the ‘70s and into the late ‘80s, the city spent up to $300 million to keep subway cars graffiti-free. “I’ve had many close calls with the police, as well as arrests, unfortunately,” ZEPHYR added.

“In one word, graffiti is vandalism. The police and the judges are not there to be art critics in any way, they just want to know if you have permission or not,”

Artists wanted to share their creative voices and the politicians wanted to silence that. This war between the city and graffiti artists became a little bit bigger than just a fight for the use of public space. Keep in mind, New York City in the ‘70s and the ‘80s wasn’t as glamorous as it is today. The city was at the tipping point of either becoming completely crime ridden or getting a fighting chance to climb back from rock bottom. And, you might’ve guessed it, graffiti artists were seen as a part of the problem.

These artists were beginning to be profiled as drug addicts and hooligans. The city took long lengths to crack down on this “vandalism crisis,” and they did so by having dogs patrol the subway yards and installed razor fences in these yards to keep them out completely. Other than going after graffiti artists, police also went after people who were break dancing in the subway and throwing huge underground parties in the Bronx. These two contributors, along with graffiti, are all contributors to the birth of what we now know as hip-hop culture. Little did police know they were trying to stop such an ongoing influential culture that still stands tall today.

As time went on during this battle, artists [of course] didn’t back down, and they began to become noticed despite the city’s efforts to try and shut them up. The healthy competition amongst the artists was to keep going, as they wanted to make sure their work was seen everywhere. Artists would get recognized for their work through the word of mouth and from seeing it around the city, and as a result, they gained the ability to sell their pieces and/or have exhibitions for their work. “The first piece of art I sold was at the age of 16. I sold a 6-foot orchid painting for $500, and I was like, ‘Oh cha-ching, these little hands can do more than just damage,’” Lady Pink noted. More and more artists would go on to get their work purchased or exhibited, like ZEPHYR’s creations that were held in NYC galleries like the FUN Gallery, and Lee Quiñones' first international exhibition in 1979.

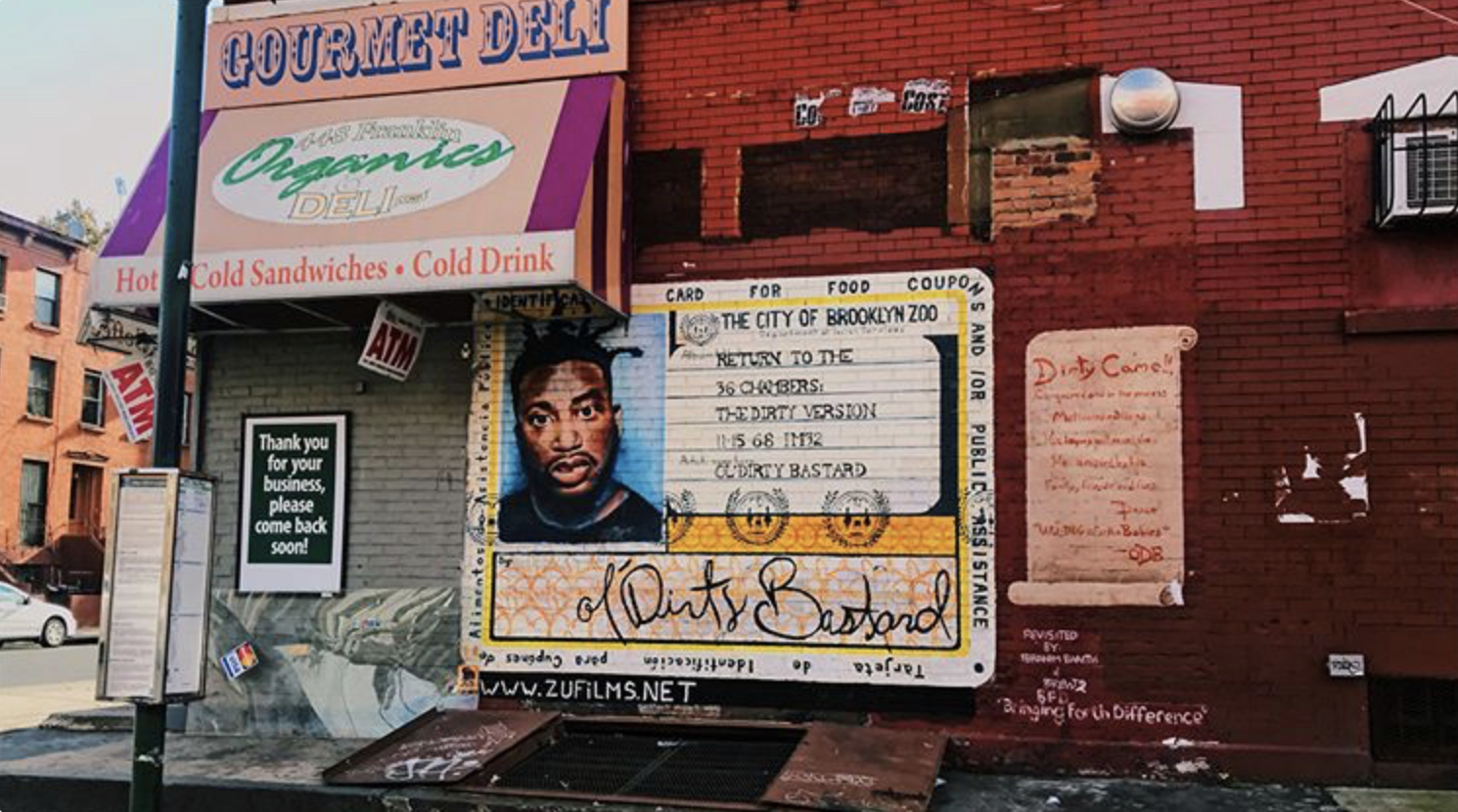

This leads us to where we are today: people want to see graffiti. People are asking to get graffiti painted on their business building’s walls. People are asking for canvases to hang in their homes. Parts of Brooklyn like Williamsburg are covered in slapped on graffiti from real estate brokers who banked on gentrification. We’ve all passed by (and if you haven’t, you should) the murals dedicated to NYC legends, like the Notorious B.I.G. mural in Bed-Stuy, the Tribe Called Quest mural in St. Albans, and the Ol’ Dirty Bastard mural on Franklin Avenue in Brooklyn.

Sources: Author's Original Photos

We’ve also seen (again, if you haven’t, you should) the murals in the city, like Banksy’s Hammer Boy on the Upper West Side, the Audubon Mural Project in Washington Heights, and the Houston Bowery Wall which Keith Haring, another graffiti legend, first contributed to. These murals are also powerful in their own ways, too. The Audubon Mural Project, specifically, was created as a call for ending global warming, starting with us. The birds seen within the mural are over 300 North American bird species that are threatened by global warming. As of right now, there are 67 birds painted, but there’s more to come. Click here if you would like to support and learn more about the project.

Several artists around New York City were paid to make these murals, or, at the very least, were given permission to do so. They didn’t have to worry about a cop coming to catch them. Graffiti, or street art, rather, is now adding property value instead of decreasing it. People want graffiti, period, and this is a plus for artists because they can make a living doing what they love.

Lady Pink has gone on to do several amazing things, like having her work displayed in museums, such as the Whitney Museum and the MET, as young as the age of 21. Now, she is getting commissioned to create from left to right. She’s doing a collaboration with high-end fashion brand Louis Vuitton for a limited time only hand-painted sneaker by Lady Pink herself. There will also be a gallery exhibit for it in Milan in June of 2022, and she will be contributing original pieces of work for that as well. She also has three mural projects coming up with local schools in NYC, including the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts in Queens. “I love working with teenagers. They are artistic, motivated, and talented. They want to be there, and they want to paint giant murals in the street.”

A New York local graffiti artist that goes by the name of Sphere has been doing commission pieces for some time now. “I’ve most recently designed a window piece on the 83rd floor of the World Trade Center,” he mentioned. “I’ve also had my work displayed in the Four-Seasons Hotel located in Beverly Hills, California.” As of recent, Sphere is taking a step back from graffiti and focusing on his passion for hip-hop. He is working on his first solo single that is about to release on December 6th, which is also his birthday.

“I think it’s every artist’s dream is to do what they love as a career,”

ZEPHYR continues to do great things as well. “I still paint trains, so it’s been an ongoing saga since 1977. You can view a lot of my trains in the “freight” section of zephyrgraffiti.com.” He also continues to tell his stories and recollections of what it was like being in this world, a lot also written on his website. ZEPHYR is also appearing on two documentaries that are airing on Showtime this month. He will be seen in the film Rolling Like Thunder, a film that dives headfirst into the underground culture of graffiti and all its glory. He will also be making an appearance in the Ricky Powell film, The Individualist. From the Beastie Boys to Madonna, Powell was able to capture the music, art, and fashion scenes of the 1980s and 1990s. He was not just capturing the scene; he was a part of it.

Now, we still have that question to answer: how did we go from arrests to hiring and compensating people for the same artwork? What clicked in people’s minds to accept graffiti after long hours of artists hiding while doing their work and trying to defend themselves from police dogs? Why didn’t we allow the passionate artists at the time to do what they love now knowing that they’re still doing it now? Other than the fact that the City would have saved a good chunk of change, New York City would most likely be a different place if we let them express themselves the first time around. Maybe graffiti could’ve become something as big as hip-hop culture and not just a contributor to it. Maybe graffiti could’ve become its own art course that could’ve been instituted in schools all around the world. Nobody would have to feel intimidated for doing what they love. There would no longer be any more hiding.

“It’s always art. Even when it is vandalism, it is still art. Even though it’s ugly, even though it’s just a tag by a teenager, they’re expressing something, it’s painted on a wall–it’s art,”

The truth is we will never know, and it’s because we didn’t listen to them then, and that’s all they wanted at the end of the day. The city didn’t allow these artists to outpour their fascinating creativity. The act was destroying yet beautifying at the same time while hiding but still clearly be seen. It’s a mystery that will most likely never receive its answer. The good thing, however, is that it still survived to this day. Bored and talented teens still continue to find any public canvas they can to tag their name or create a piece. It’s never too late to start listening to them now.